Abnormal reeding

This coin was struck from a collar die, which had either more than or less than the normal number of reeds. One of the most well-known examples is the 1921 Morgan dollar, which exhibits infrequent reeding.

Abrasion doubling

These coins were struck from dies that have been heavily abraded. The abrasion could have occurred inside the cavities of the design, including letters and digits. Such coins appear to have overlapping or doubled design elements. The abrasion could have occurred on the outside edges of the design, including letters and digits. The doubling is most commonly seen between the letters or digits and the rim. The best examples are the “poor man’s double dies” of 1955. These coins are NOT the product of hub doubling and carry little, if any, premium. Abrasion doubling is a very common occurrence, especially on recent coinage. Thus it has little collector interest or value. Also see Die Deterioration Doubling.

Bar die break

This is a sub-category of the die break affecting the letters of LIBERTY and the date of the Jefferson nickel. Primarily affecting the dates of 1960-D and 1961-D, this variety features a bar across the top of the letters of LIBERTY and the digits of the date. Many examples exist with just a single bar, but as many as seven bars on a single coin have been reported. Again, interest waned when the dies were modified and the variety ceased to be created.

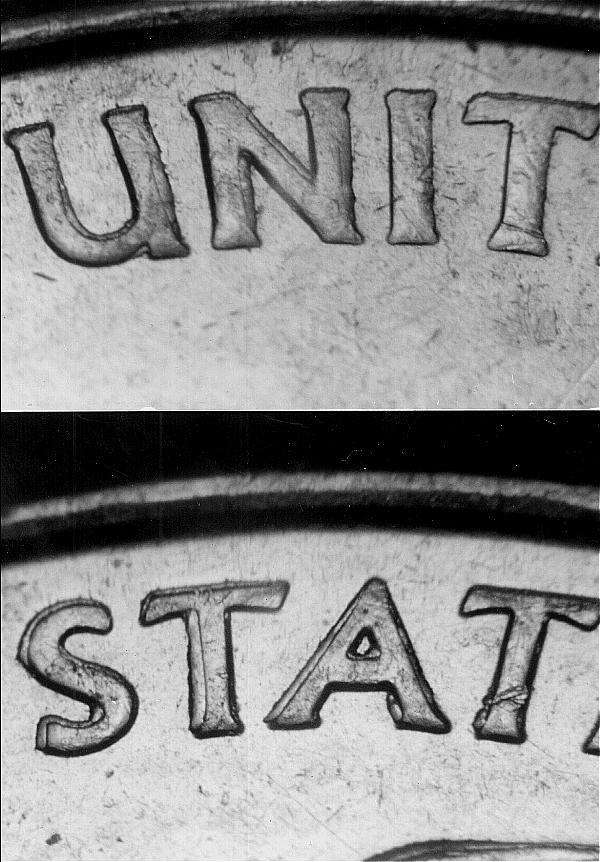

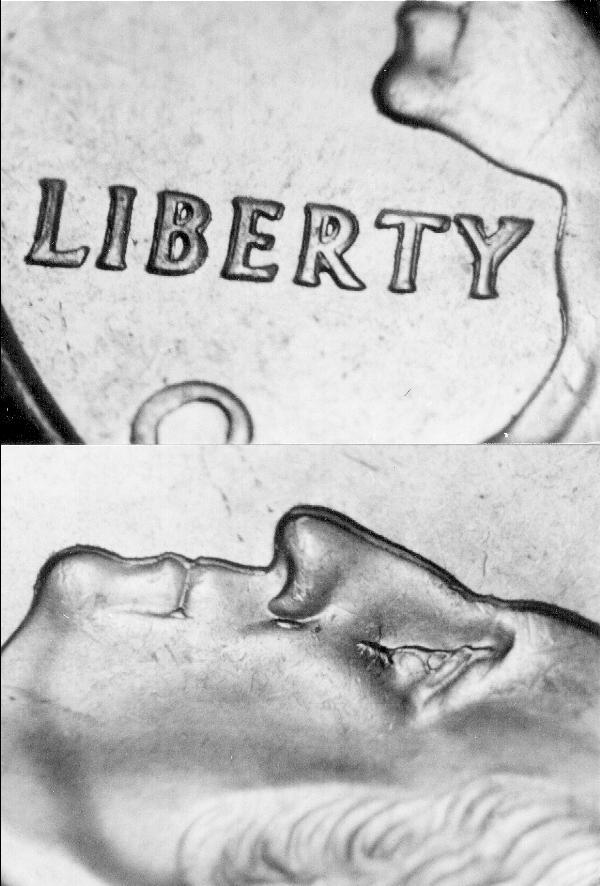

BIE die break

This is a sub-category of the die break affecting the letters of LIBERTY on the Lincoln cent. Technically, only a die break between BE of LIBERTY qualifies as a BIE. Generically speaking, however, a die break between any of the letters of LIBERTY qualifies. This variety was termed the “BIE” because that is where the vast majority of die breaks occur. This area of collecting was again the rage in the 1960s, but waned when the obverse die was modified and there were fewer specimens to collect. However, recent years have seen a new crop of this variety showing up and an increased interest.

Blank

These planchets have not passed through the upset mill. The upset mill raises or upsets the edge of the planchet for the purpose of better striking and stacking of the coins. Discs without an upset edge are correctly called blanks. They are generally assumed to be easy to fake, but recent investigations have found this to be much more difficult than first thought. No Type I copper-plated zinc cent blanks are known. This is due to the fact that the copper plating is applied after the blank passes through the upset mill.

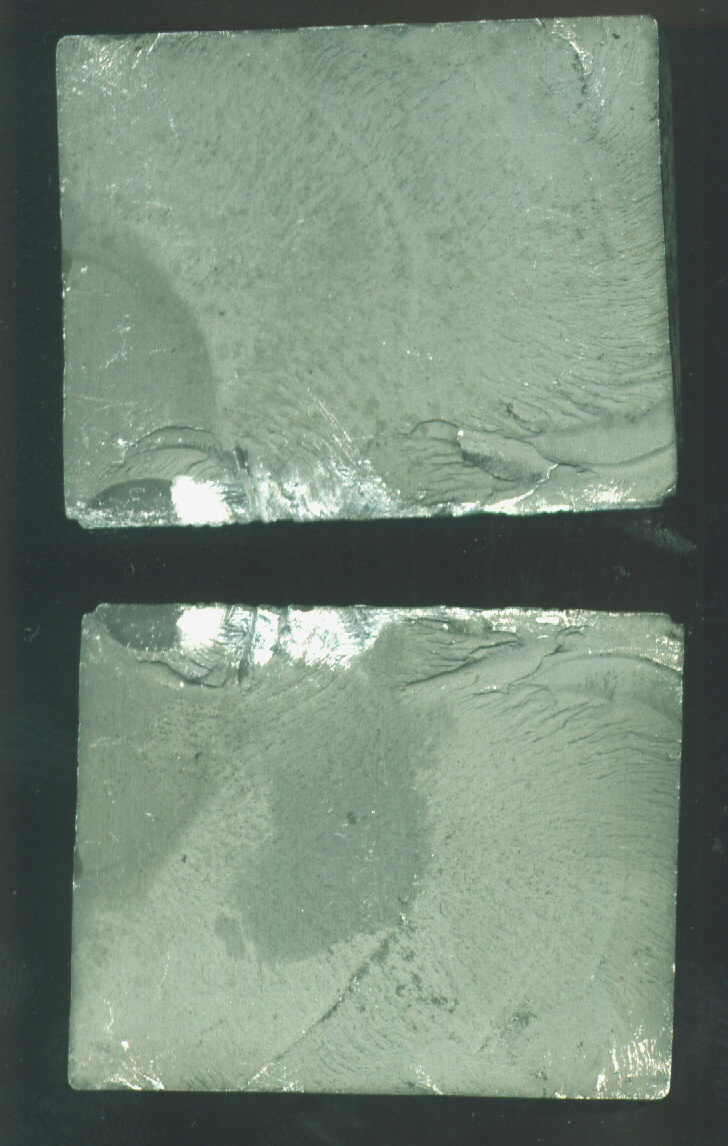

Blems

“Blems are much larger mounds of raised metal [than E.D.M. Spikes] on a counterfeit coin. They are found at random, if at all. It is not known if they are the result of poor die steel, poor handling of dies, or by incorrect operation of E.D.M. equipment. Average size of a blem is .008″. The blems will result from pits in the die.” (Lonesome John Devine, Detecting Counterfeit Coins — Book 1, Heigh-Ho Printing Co., 1975, page 7). The term is sometimes misapplied to genuine coins to describe pits in the die due to rust or other forms of deterioration (though it may be applied to genuine coins, tokens or medals originating from E.D.M. dies).

Thai1971 50baht w/Counterfeit Off Center 2nd Strike showing numerous spikes and blems

Thai1971 50baht w/Counterfeit Off Center 2nd Strike showing numerous spikes and blems

(photo by Ken Potter / Coin courtesy of Mark Longas).

Bonded planchets

Occasionally, two planchets bond and are struck together in the striking chamber. In a couple of instances, as many as 30 or 40 planchets have been bonded together in the striking chamber. These make for fascinating conversation pieces

Brockage errors

Brockage errors are the result of a planchet and a normally struck coin being in the coining chamber at the same time. The two items may overlap each other, rest on top of each other, or be of different sizes. There is one exception – the “brockage second strike” – which is the result of a planchet and a brockage coin being in the coining chamber together. When a coin sticks to the upper or lower die a number of brockage strikes may occur from the same coin (which at this stage is known as a “die cap”). The first strike from the “capped die” will result in a “mirror brockage” that will exhibit a perfect incuse mirror image of the design. As the cap continues to strike coins it will distort and spread outward wrapping itself around the shank of the die looking very much like a soda bottle cap or in later stages like a thimble. This will result in the designs of the coin closest to the rim eventually no longer appearing on the brockage strikes that result from the distorted cap.

Great Britain Elizabeth Young Head Penny First-Strike Mirror Brockage

Great Britain Elizabeth Young Head Penny First-Strike Mirror Brockage

(Photo courtesy of Ken Potter / Coin courtesy of Mark Longas).

Great Britain 1818 6-pence Mid Stage Brockage

Great Britain 1818 6-pence Mid Stage Brockage

(Photo courtesy of Ken Potter).

No Date Clad Roosevelt Dime Mid to Late Stage Brockage

No Date Clad Roosevelt Dime Mid to Late Stage Brockage

(Photo courtesy of Ken Potter).

Brockage second strike

When a brockage coin rests partially on a planchet, the result is a “partial counter-brockage strike” coin and a double struck coin that has a second strike off-center and a corresponding depressed and slightly enlarged incused mirror image of the already struck coin on the opposite side.

Brockage strike of a smaller coin or coin fragment

When a planchet and an already struck smaller coin or fragment are in the coining chamber together, the result is a double struck image on one side of the smaller coin or fragment and a flattened, enlarged design on the other side, and a second coin with a strong strike on one side and a depressed and slightly enlarged incused mirror image of the already struck smaller coin or fragment on the other side.

ND Indian Head Cent Struck Thru Strk Fragment

ND Indian Head Cent Struck Thru Strk Fragment

(Photo courtesy of Ken Hill).

Brockage-counter-brockage errors

These are the most complicated errors of all. They are also some of the rarest and most valuable striking errors. They are the result of a planchet and a counter-brockage strike coin in the coining chamber together.

Broken letter or digit on an edge die

Lettering on the edge of a coin is normally incused. Thus the die that produced the lettering is normally in relief. Once a letter or digit breaks off either in part or in whole, all coins struck thereafter by that collar die exhibit those broken or missing letters or digits. The use of a broken punch while producing the edge hub results in a coin exhibiting the same characteristics. In this case, however, all coins have the broken or missing letters or digits rather than just a few coins

Broken planchet

These planchets have broken into at least two pieces. The break can occur either before or after the strike. A break after the strike shows sharp, rough edges with a grainy appearance. A break before the strike shows rounded-off edges and metal flow toward the break.

Bubbled plating

These planchets have gases trapped between the core material and the plating.

Capped die

This coin is the result of two planchets or a planchet and a coin being present in the coining chamber and then one of them sticking to the hammer die.

Centered broadstrike

This coin expanded well beyond its normal diameter because the collar jammed far enough down on the anvil die shaft that there was nothing to retain the shape of the coin during the strike. In this case the planchet was centered between the obverse and reverse dies.

Chain strike

When two planchets are struck while resting side by side, the result is two off-center coins, each with a flattened edge.

Clad layer—missing

These planchets are produced from clad coin metal strips with either one or both clad layers missing.

Clad layer—struck, split after strike

This is the clad layer which has split from the struck coin.

Clad layer—struck, split before strike

This is the clad layer which has split from the planchet and was subsequently struck.

Clad layer—unstruck

This is the unstruck clad layer which has split from the planchet.

Close centered double strike

This coin exhibits a dual image on both sides of the coin because it was struck by the dies a second time while remaining in, or partially in, the collar but slightly rotated from the position of the first strike

Collar break

When raised areas of metal are visible on the edge of a coin, it has been struck with a broken collar. Such a coin also exhibits two distinct curved areas, making it out of round.

Collar clash

Occasionally, the die shifts slightly out of position and, instead of fully striking the planchet, it partially strikes the collar. As with a die clash, the design of the collar, whether smooth or reeded, is transferred to the die. This, in turn, is transferred to the coins struck by the die. Most often, only the reeded collar clashed coins are of collector interest, but again, only if there is significant design transfer.

Copper washed

These planchets receive a thin chemical coating usually of copper color while going through the wash cycle prior to striking. See also Sintered.

Corrected horizontal mintmark

This is a sub-category of the RPM in which the secondary mintmark (in this case the first punch) was punched horizontally and then corrected.

Corrected inverted mintmark

This is a sub-category of the RPM in which the secondary mintmark (in this case the first punch) was punched upside down or inverted and then corrected.

Counter-brockage errors

Counter-brockage errors are the result of a planchet and a brockage coin being present in the coining chamber at the same time. The items may overlap or rest on top of each other. There is one exception – the “counter-brockage second strike” – which is the result of a planchet and a counter-brockage coin being in the coining chamber together.

Counter-brockage second strike

This is the exception to the one planchet and one brockage struck coin rule. When a counter brockage coin rests partially on a planchet, the result is a “partial brockage-counter-brockage strike” coin (described below) and a double struck coin with the second strike off-center and a corresponding depressed and slightly enlarged relief image of the already struck coin on the opposite side.

Crescent curved clip

These planchets are formed from the smaller portion of an incompletely punched curved clip that has separated.

CUD

See Major Die Break and Retained broken die.

Defective Planchet

These planchets have cracks or holes.

Design hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of a hub with a slightly different design being used for the subsequent hubbing. Because of a similarity in the design, the doubling is usually sporadic and localized. However, designs can have enough differences that the doubling is widespread, as in the case of some overdates. One of the nicest examples is the 1960-D small over large date Lincoln cent. See hub doubled varieties.

Design modifications and pairings

The design of a given series is often modified to enhance the minting process. Sometimes the relief is lowered or heightened. Sometimes certain fonts are changed (e.g. large date and small date). Sometimes certain weak elements of the design are strengthened so that they will show up better on the coin. Each new modification requires a new master die be produced.

Die adjustment

These coins were struck during the adjustment period while the pressure of the strike was too low to fully bring up the design. Only parts of the central design show on each side of the coin. Care should be taken to distinguish this error from the “weak strike” and the “struck-through” errors. An adjustment strike reeded edge coin exhibits weak reeding as well as a weak design

Die break

These are large raised irregular blobs found usually at the design stress points. They are most often found in the fields between the design and the rim. After repeated strikings under tons of pressure, the dies begin to crack. When these cracks meet each other (as in a circle), or when they extend to the rim, the metal contained within the borders of the crack begins to break away from the die itself. The broken piece may not at first be loose enough to fall away. In such a case, the coin shows a depression where the die chip or, if it is large enough, the die break has occurred.

Die chip

These are small raised irregular blobs of metal found usually at the design stress points. They are most often found in the recessed areas of certain letters or numbers (e.g.; B & R of LIBERTY and the 9 & 5 of the date). This is because the recessed areas of the letters and numbers on the coin are raised areas on the die, which look like little islands. It does not take much stress before these raised pieces of the die start to chip and break off, leaving a raised area on the coin where a recessed area is expected.

1918-S 1c w/die chips in Mint mark.

1918-S 1c w/die chips in Mint mark.

(Coin courtesy of James S. Bailey/Photo by Ken Potter)

Die clash

For the wheat cent, look under Lincoln’s chin for an upside down T of CENT on the obverse and between the E of ONE and the N of CENT for Lincoln’s tie on the reverse. For the Memorial cent, look for the vertical columns of the memorial building both in front of and behind Lincoln’s head, as well as for the horizontal building lines through the 1 of the date. (These have recently been promoted as “prisoner” cents because the clash makes Lincoln appear as if he were behind bars). On the reverse, look in the first three bays of the building for an incused and upside down RTY of LIBERTY. Also, often Lincoln’s head can be seen through the letters of ONE CENT.

1999-D 1c with clash marks

1999-D 1c with clash marks

(Coin courtesy of William A. Gesell/Photo by Ken Potter)

1985 1c exhibiting double clash marks

1985 1c exhibiting double clash marks

(Coin courtesy of Tim Wissert/Photo by Ken Potter)

Die crack

These coins exhibit raised irregular lines as a result of a crack in the die.

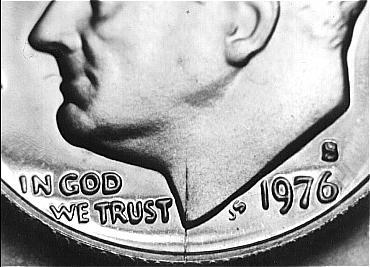

1976-S Proof Dime Die Crack

1976-S Proof Dime Die Crack

(Coin and photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Die dents

A dent is considered to be an impairment that does not break the plane of the die. It appears on the coin as a slightly raised area.

(Dies and photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Die deterioration doubling (DDD)

DDD is the result of heavy die-use or improper heat treat (of the die) combined with die-use. Die-use eventually causes deterioration of the die steel and may manifest itself as doubling, thickening, twisting, “patches” and other deformities usually most pronounced on lettering or other designs closest to the rim but it may progress to more centralized areas in later stages. It is often found in combination with heavy die flow lines or irregular fields, (referred to “orange peel),” though it may show exclusive of these characteristics if the fields were recently stoned or otherwise dressed-out to remove such superficial defects. Another school of thought refers to this form of doubling as “Abrasion Doubling.” No matter what is called the vast majority of variety coin specialists consider it worthless since it is considered normal to die-use and too dynamic to catalog as a variety.

(Coin courtesy of Dwane Bauer/photos by Ken Potter)

(Photo courtesy of J.T. Stanton)

Die gouges

These are raised thick bulges, usually on the fields of a struck coin (although they may occasionally be seen on the design), which are created by the striking of a hard object against the die. This object could be another die, a hammer, or even a grinder.

(Photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Die progression

These coins are from the same die pair that exhibits a change in the appearance, strength, or number of any category of die errors.

Die repeat

Frequently, undated dies are used in the following year. Through die markers, coin pairs can be assembled where two different dated coins have a common reverse die. (All regular issue U.S. coins had dates on the obverse until the States Quarters Program was introduced). Doing so requires the right timing and a lot of patience. One example, however, where the search is easier, is the proof 1940 Jefferson nickel with the reverse of 1938. The reverse of this coin exhibits a nice doubled die as well as the easily recognizable wavy steps. The kicker is that this same doubled die is known on a 1939 dated proof, providing the second coin for the die repeat pair.

Die rust

Early U.S. coinage dies, collars, and hubs were especially susceptible to rusting. With modern technology and environmental control, this has virtually been eliminated. Remember that pitting on the die results in raised bumps on the coins.

Die scratches

These are raised thin lines, usually on the fields of a struck coin (though they may occasionally be seen on the design), which are created by the abrading of a die. It is the pattern of the die scratches which makes them important. Die scratches are often used for identification of a stage for a particular variety. The pattern acts like a fingerprint, pinpointing an exact position in the die progression.

Die substitution

These coins have one die in common. Often in the abrading of the dies, they are reinstalled in the press with a different mate. This is most often the case when one of the dies in a pair has reached the limit of its usefulness and is replaced by a new die.

Different denomination die clash

These coins were struck from a die that had clashed with a die of a different denomination. One of the best examples is the 1857 Flying Eagle cent that was clashed with a Liberty Seated half dollar.

Disc clip

These incomplete planchets are sometimes called “rim clips” because they are so small that only the rim is affected. Often the rim is fully upset and the resultant coin shows very little missing metal. Clad planchets show a reversal of the clad layer on the edge. Technically, the term “disc clip” is reserved for clad coinage and the term “rim clip” is used for non-clad coinage. In practical usage they are synonyms.

Displaced mintmark

This coin was struck from a die in which the mintmark was positioned far enough out of place to be touching a design element.

Distended hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of the raised images on the hub becoming flattened and thicker than normal. When one normal hub is impressed into the die, and then is followed by a flattened hub, the resulting image is much thicker than normal. On extreme examples, you can see notching of the serifs. However, normally all that can be seen is extra thickness to the letters and digits. Being able to quickly detect this kind of hub doubling requires a firm mental image of what a normal coin looks like. See hub doubled varieties.

Distorted hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of a die or hub expanding during the annealing process and not returning to its original size. An expanded die matched with a normal hub results in doubling toward the center. An expanded hub matched with a normal die results in doubling toward the rim. See hub doubled varieties.

Double Denomination

See Struck over a different denomination or series.

Doubled Die

See Hub doubled varieties.

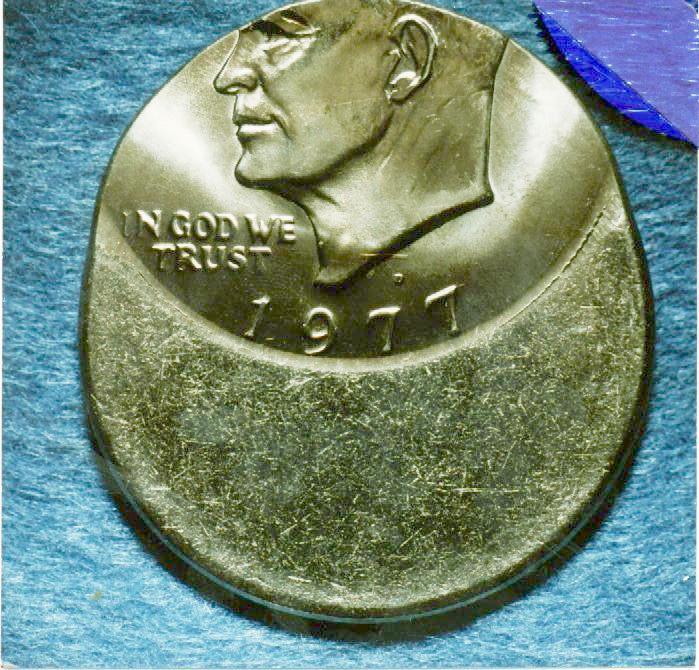

Double Strike 1st strike centered; 2nd Off Center

Edge Strike

These coins were struck while the planchet was standing on its edge in the coining chamber. The faces of the planchet are blank, while small parts of the design show on the flattened edges.

Edge Variety

Any variation of the edge created by intent or error that results in differences of the edge design such as (but not limited to) the number or style of reeds, ornamentation, position of edge lettering, etc. This term also encompasses “Abnormal reeding.” See Abnormal reeding.

(Photo by Ken Potter)

Flat field doubling

This coin exhibits dual images as a result of having its machine doubled image flattened by the second strike of a proof coin. This is a very common phenomenon on proof coins from 1950-1974. See also Second strike doubling from a loose die.

Flip over double strike

See Obverse struck over reverse.

Folded planchet strike

This coin exhibits a dual image, the first of which was made while the coin was standing on its edge. The planchet folded, and a second image was created in the same stroke of the dies.

Full brockage strike

When a planchet and an already struck coin rest on top of each other in the coining chamber, the result is one coin with a depressed and slightly enlarged incused mirror image of the already struck coin on one side and a strong strike on the opposite side, and a second coin with a double strike on one side and a flattened, enlarged relief design on the opposite side.

Full counter-brockage strike

When a planchet and a brockage struck coin rest on top of each other in the coining chamber, the result is one coin with a depressed and enlarged relief image of the already struck brockage coin on one side and a strong strike on the opposite side, and a second coin with a double strike on one side and a flattened, enlarged incused design on the opposite side.

Heavy die transfer

When a die nears the end of its usefulness, often it exhibits the major central design of its opposing mate. This design is transferred from one die to the other through the striking of the coin metal. Alan Herbert gives this illustration: “The best example I can offer of this phenomenon is the toy which you’ve all seen which has five or six metal balls hanging in a row, touching each other. When you pull back the end ball and allow it to strike the row, it causes the ball at the far end to swing away from its neighbor. The same thing occurs with design transfer, the outline of the design being transferred from one die to the other.” (Alan Herbert, Minting Varieties and Errors, fifth edition, New York: House of Collectibles, 1991, page 158). This variety is fairly common on the early wheat cents. It is often called the “ghost of Lincoln.” The technical term for this is IMPD (Internal Metal Displacement Phenomenon).

Hub break errors

These coins exhibit a missing portion of the design or an incused area of the field due to a break on the hub. Because the hub affects many working dies, once a hub break occurs it is easy to find an example of the coin. As a result, they generally carry no additional premium.

Hub doubled mintmark

This is a sub-category of the doubled mintmark, but it is not an RPM. Since 1985 for proof coins and commemoratives and 1990-1991 for circulation strike coins, all mintmarks have been placed on the master dies. Consequently, the mintmark can only be doubled if there is hub doubling present. In the ten years since this practice began, less than six examples are known, with the first two circulation strike examples showing up in 1995 on the Lincoln cent.

Hub doubled varieties (doubled dies)

The hubbing process, while rather simple in its procedure, is rather complex in the varieties that it produces. Once the master die (incused image) is created (a process not completely relevant at this point), it is used to hub or squeeze a working hub (relief image), which is in turn used to hub a working die (incused image). Since one hubbing is not usually enough to bring up a sharp image, the die is annealed (softened by heat) and re-hubbed, occasionally multiple times. If the working hub and working die with its initial image are not fitted together properly in the press, a doubled image occurs on the die. This doubled die will in turn transfer a doubled image to every coin it produces. While much has been made of the way in which a doubled die is produced (the complex part), the important thing is to be able to recognize the characteristics of hub doubling. These characteristics include raised, rounded images with splits in the serifs and valleys or furrows between the images. These are the same characteristics as found on repunched dates and repunched mintmarks. Being able to distinguish hub doubling from “machine doubling damage” (sometimes called “ejection doubling,” “mechanical doubling,” or “strike doubling”) is a mark of the advanced variety collector. However, anyone can learn the difference if they are willing to take the time to study the photos and the coins.

In its infancy, the collecting of hub doubled coins, commonly known as “doubled dies,” centered around the circumstances that produced the various kinds of doubling known. For example, the doubling on some coins appeared all the way around the rim lettering in a clockwise or counter-clockwise fashion. Other coins exhibited doubling on just some of the rim lettering. On other coins, the doubling was directed toward the center or the rim. Still on others the doubling affected only certain design elements. Thus the following classes of hub doubling were proposed, principally by Alan Herbert, to explain these differences. Most hub doubling is now regarded as a hybrid of these classes. It is very difficult with only a coin in hand to logically backtrack and find the cause of its hub doubling. So many things can and do happen in the hubbing process that figuring out exactly what happened in each case may not be possible. Again, the important thing is recognizing the variety as true hub doubling, not in determining to which class of hub doubling it belongs. See Rotated hub doubling, Distorted hub doubling, Design hub doubling, Offset hub doubling, Pivoted hub doubling, Distended hub doubling, Modified hub doubling, and Tilted hub doubling.

Improper alloy mix

These planchets usually have irregular streaks from an incomplete mixing of the metals. These are common on the early wheat cents.

(image courtesy of Whaden Curtis)

Improperly annealed

If a planchet failed to be annealed (the process of softening the metal by heating), or was annealed improperly, it will retain its hardness and result in a poorly struck coin.

Included Gas Bubble

Gases from the melting of the alloy may become trapped, producing bubbles in the planchet.

Incomplete cladding

These planchets are produced from clad coin metal strips that have holes or gaps in the clad layers.

Incomplete curved clip

These planchets have a curved cut that does not penetrate to the other side. An incompletely punched clip shows the cut on both sides of the coin.

Incomplete straight clip

These planchets are punched across the incomplete shear at the end of the coin metal strip. No example of this error is currently known.

Indent errors

Indented errors are caused when two planchets are in the coining chamber at the same time. The two planchets may overlap each other, they may rest on top of each other, or they may be of different sizes. There is one exception—the “indented second strike”—which results from a planchet and a struck coin coming together in the coining chamber.

Indented by smaller planchet

When two planchets of different sizes are in the coining chamber, the result is a uniface smaller coin with a strong strike on the die side and a second coin with a shallow, irregularly rounded depression on one side and a strong strike on the opposite side.

Indented second strike

When an already struck coin rests partially on a planchet, the result is a “partial brockage strike” coin and a double struck coin with the second strike off-center and uniface.

(Coin and Photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Indented strike

When two planchets overlap each other in the coining chamber, the result is one coin which is a uniface off-center (sometimes called a “stretch strike” because the extra pressure forces the planchet into a larger-than-normal shape) and a second coin with a shallow, irregularly rounded depression on one side caused by the other planchet receiving the strike from that area of the die.

Inverted mintmark

This coin has a mintmark which was punched in upside down but not corrected. The only known examples have been on the S mintmark.

Laminated die

Dies like planchets have been known to laminate. Thin layers of the die metal peel up, allowing the planchet metal to flow under them. Coins struck from a laminated die show a die crack with a corresponding depression where the laminated die was forced up against the planchet. Examples are extremely rare.

Lamination crack

These planchets have pieces of metal “peeling” from them. The lamination can be completely missing or retained on the planchet. The larger the lamination, the greater the rarity. Laminations are frequent on the 35% silver war nickels of 1942-1945. They are common on wheat cents, but are rather rare on 90% silver coinage.

Large over small mintmark

This is a sub-category of the RPM in which two different sizes of mintmark punches were used and the secondary mintmark is the smaller of the two.

Machine doubling damage (MDD)

This NOT a form of hub doubling. The secondary image is flat and shelf-like, with rounded-out serifs. There are no valleys or furrows between the images. When tilted, the area between the two images is shiny. The light reflects off of sheared metal. Because the metal is actually sheared or moved, this form of doubling is considered damage to the coin and commands NO premium. This form of doubling is also referred to as “Strike Doubling” or “Mechanical Doubling” by others.

MAD

Misaligned die. See Offset Die Misalignment.

Major die break

This is a further sub-category of the split die. When a broken piece of a split die completely separates from the die and falls away, the result is commonly called a “cud.” Because of a lack of pressure, the planchet metal flows into the broken area of the die, creating a weakened image on the opposite side of the coin. Major die breaks have been actively collected for many years. They are most commonly found on Lincoln cents, but are known on many denominations. Major die breaks on halves and dollars are considered rare. Logically, the larger the die break, the larger the premium.

(Dies courtesy of Ken Potter)

(Photo/coin courtesy of Ken Potter)

Matched pair

These coins are from similar strikes, but do not fit together perfectly.

Mated pair

These coins were struck together in the coining chamber. They fit together perfectly.

Mintmark styles: small, large, broken, doubled punch

Many different mintmark styles or fonts have been used through the years. A few years exhibit two or even three different styles, some of which are considered very rare. . All doubled mintmarks for the 1974-S coinage are from a doubled mintmark punch. Because these coins are so common, NO premium should be paid for the doubled mintmark.

Mismatched die strike

This coin exhibits obverse and reverse designs that normally do not belong together; that is, they are for two different coins. This error is commonly referred to as a “mule.” Until recently the only known U.S. “mules” were pattern strikings. The U.S. first circulation strike “mule” has now been confirmed. It is a States quarter obverse matched with a Sacagawea dollar reverse. Several foreign “mules” are known. Beware of “magician” coins that have been altered outside the mint. Most common are the two-headed coins and the cent and dime combination. It is impossible for either of these to be produced in the U.S. Mints.

Misplaced dates (MPD)

This is a sub-category of the Repunched Date (RPD), where the secondary image is either completely separated from the primary image and/or the secondary image is touching a design element such as the legend, devices, or denticles. Sometimes MPDs are referred to as “blundered dates” or “blundered dies.”

(preceeding images courtesy of Whaden Curtis)

Modified hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of a modification of the hub, either by repunching or by grinding off an undesirable design element. Since hubs are used to make impressions in thousands of dies, it would be a waste to throw out an otherwise perfectly good hub. So the undesirable design element is ground off and the resulting modified hub is used to make the initial impression(s) in the dies. A hub with the complete design is used to make the final hubbing of the dies. The doubling occurs when the undesired design element is not completely ground off and traces of the design still remain. These traces show up as doubling on the finished die even though a complete hub was used for the final impression. Since this form of doubling originates with a hub, several working dies will exhibit the same type of doubling. The best examples are the 1970 Lincoln cents on which all three mints are represented by specimens of the “Low 70/Level 70” dates. The initial impression on the dies was from a modified hub bearing the “Level 70” date. The final impression was from a hub bearing the full “Low 70” date. See hub doubled varieties.

Mule

See Mismatched die strike.

Multiple clip

These planchets have more than one curved clip. Obviously, the more clips the greater the rarity. However additional premiums depend upon the amount of missing metal.

Multiple strike

This coin exhibits more than two images because it was struck multiple times by the dies in any size or any location of strike.

(Coin courtesy of Carl Herkowitz/photo by Ken Potter)

Non overlapping double strike

There are two possibilities for a coin having dual nonoverlapping images on both sides of the coin. First is that the coin is actually double struck with the second strike simply being far enough off-center to fail to overlap the first strike. The second is that the coin was “saddle struck.” The saddle struck coin is so designated because the planchet saddles the die pairs (is positioned so that part of the planchet falls under each set of dies) in a dual or quad press. Thus, with one stroke of the press, two images are placed on the planchet. This is considered a double strike because two die pairs are involved.

Obverse struck over reverse

This is often referred to as the “flip-over double strike.” This coin exhibits a dual image on both sides of the coin because it was struck twice by the dies; however, the image is obverse over reverse on one side and reverse over obverse on the other side because the planchet “flipped” between strikes.

(Coin and photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Off center die clash

These are coins that were struck from dies that were misaligned when they clashed. The best example is on the reverse of an 1880 Indian cent.

(Dies courtesy of Ken Potter)

Off center second strike over a centered first strike

This coin exhibits a partial dual image on both sides of the coin because it was struck by the dies a second time while remaining only partially under the dies

Off-center second strike over an off-center first strike

This coin exhibits a partial dual image on both sides of the coin because it was struck twice by the dies with the planchet being only partially under the dies for both strikes. This category, by definition, is limited to double strikes that overlap. See also Nonoverlapping double strike.

Offset Die Misalignment

This coin exhibits what at first appears to be an off-center strike; however, the opposite side of the coin is in perfect alignment. This error occurs when a die (usually the hammer die, but occasionally the anvil die) is offset in any direction. In order for the error to have any significant collector value, it must have a portion of the design missing. Typical examples of this error type will range between 2% to 5% Off. This error is often called a Misaligned Die, or MAD for short.

(Medal courtesy of Ken Potter)

Offset hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of a hub or die being offset in any direction from the center of the design. The doubling is spread across the entire design in the same direction. See hub doubled varieties.

Omitted mintmark

This coin was struck from a die in which the mintmark had been omitted. Several examples exist in modern proof coinage. Circulation coinage sports two examples: the 1922 plain Lincoln cent and the 1982 No P dime.

Oval curved clip

These planchets are formed from the larger portion of an incompletely punched curved clip that has separated. These are sometimes referred to as “elliptical clips.”

(Coin and Photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Over mintmark (OMM)

This is a sub-category of the RPM in which the secondary mintmark (in this case the first punch) came from a punch intended for a different mint.

Overdate

This is another sub-category of the Repunched Date (RPD). In this instance, the digits of the secondary image are not the same as those of the primary image. Remember that all U.S. overdates after 1901 are the result of the hubbing process rather than the punching process. The only known inverse date on a U.S. coin is the 1853/4 quarter.

Overlapping curved clip

These planchets have two curved clips that overlap each other

Partial brockage strike

When a planchet and an already struck coin overlap each other in the coining chamber, the result is an “indented second strike” coin and a second coin with an irregularly curved, depressed, and slightly enlarged incused mirror image of the already struck coin on one side and a strong strike on the opposite side.

Partial collar

This error is commonly called the “railroad rim” even though it is the edge, not the rim, that is affected because it looks like a railroad car wheel. This coin exhibits a split-level edge where the obverse (hammer die strike) has expanded larger than the reverse (anvil die strike). This occurs when the collar jams on the shaft of the anvil die at a position where only part of the planchet is contained in the collar. Care should be taken not to confuse this error with a coin that has been damaged by being forced into a “lucky” coin holder. The partial collar strike has two distinct diameters. See also Reverse partial collar, Tilted partial collar.

Partial counter-brockage strike

When a planchet and a brockage struck coin overlap each other in the coining chamber, the result is a “brockage second strike” coin (described above) and a second coin with an irregular curved, depressed, and slightly enlarged relief image of the already struck coin on one side and a strong strike on the opposite side.

Partially plated

These planchets have a portion of the core material exposed because of an incomplete plating.

Pivoted hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of a pivot of the hub or die at or near the rim in either a clockwise or counter-clockwise direction. The doubling spreads out in a fan shape from the pivot point. The strongest doubling is at the rim directly opposite the pivot point. See hub doubled varieties.

(Coin courtesy of Richard Bateson/Photos by Ken Potter)

Planchet

These planchets have passed through the upset mill. They have a raised edge, but no reeding. Reeding is placed on the planchet as part of the striking process (reeded collars). Edge lettering has been applied prior to the strike, during the strike, and after the strike.

Ragged clip

These planchets are punched from the unsheared or unsawed end of the coin metal strip.

Railroad rim

See Partial collar, Reverse partial collar, Tilted partial collar

Repunched dates (RPD)

This variety is often called the RePunched Date (RPD). It describes a coin from a die on which the date has been repunched with the same digits but in a different position.

(Coin courtesy of Larry Allegrina/Photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Repunched Letters (RPL)

These coins exhibit lettering that has at least a doubled image on one or more letters due to repunching. Because it is nearly impossible to tell which punch was first, the strongest punch is considered the primary and the lightest punch is considered the secondary. Often incorrectly refereed to as “reengraved.”

(Coin courtesy of Brian Rains/Photo credit Ken Potter)

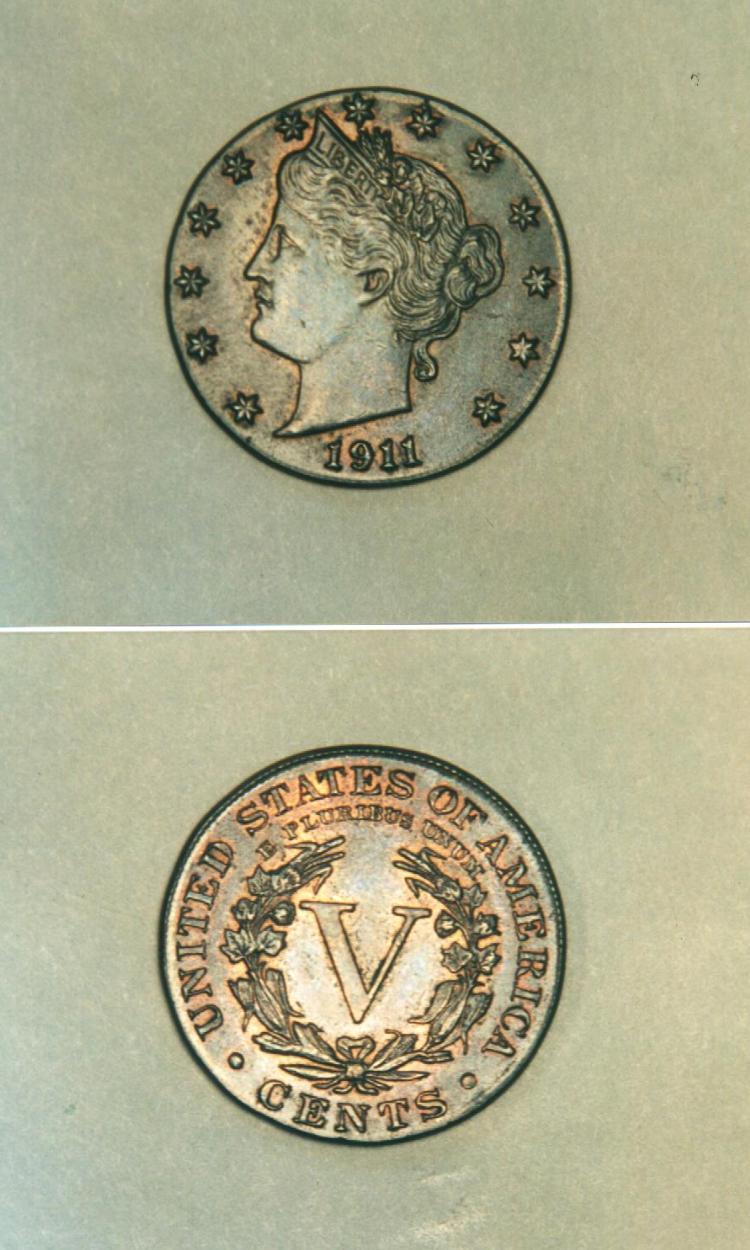

Repunched mintmarks (RPM)

These coins exhibit a mintmark that has at least a doubled image due to its being repunched. A large segment of the hobby is devoted to the collecting of these mintmark varieties so they are given a separate section even though they technically belong under “Repunching Varieties.” Because it is nearly impossible to tell which punch was first, the strongest punch is considered the primary mintmark and the lightest punch is considered the secondary mintmark.

(Photo courtesy of Frank Zapushek)

Retained broken die

This is a sub-category of the split die. The broken piece of a split die may be held in place either because it is not fully separated or because it is part of the anvil die. The anvil die is the die on the bottom (for Lincoln cents this is the reverse die) and is surrounded by the collar, which acts as a retaining wall for the broken die. The coins produced from such a broken die show the portion of the die that has broken away as a raised area, like a plateau. Coins that have raised areas extending to the rim are commonly called “retained cuds.”

(Image courtesy of Whaden Curtis)

Reverse partial collar

Here, it is the reverse that is larger in diameter than the obverse. The reason is a switch in the hammer die from obverse to reverse. This is a rather rare error because most U.S. dies are positioned with the obverse as the hammer die. Some exceptions are the Buffalo nickel, Mercury dime, and Peace dollar. See also Partial collar, Tilted partial collar.

Rim clip

See Disc clip.

Rim die break

These are raised blobs found on the design rim of the coin. By definition, the rim does not include the field or denticles. If the break extends into these areas, the variety is classified as a major die break (Cud). Rim die breaks are fairly common and rarely command a premium

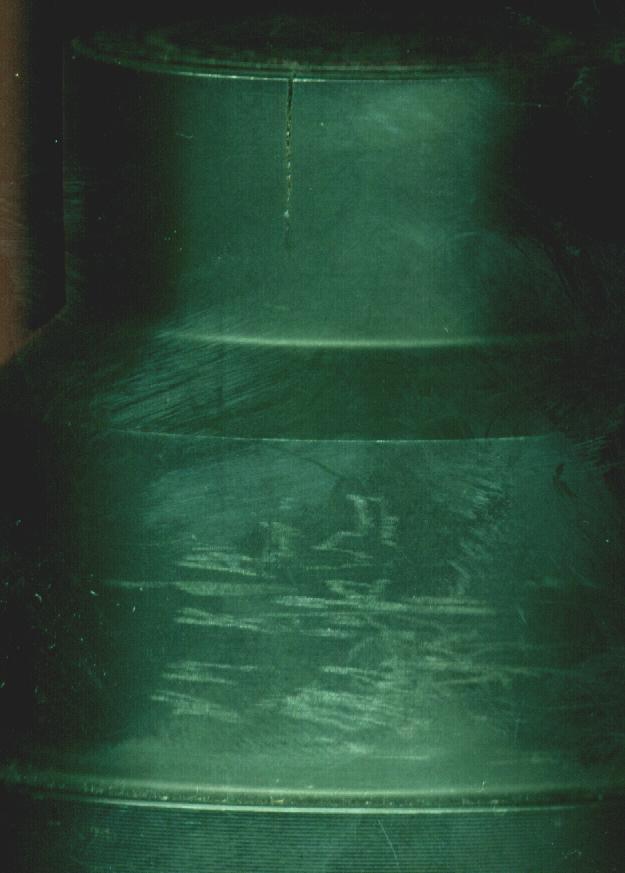

Rim to rim die crack

This is another sub-category of the die crack. The die crack has extended to the point that it connects two points on the rim. They may be at opposite ends of the die or they may be close together.

(Die courtesy of Ken Potter)

Rolled thick

These planchets are punched from coin metal strip that is too thick for the desired coins.

Rolled thin

These planchets are punched from coin metal strip that is too thin for the desired coins.

Rolled-in metal

These planchets are punched from coin metal strip in which a piece of metal has been rolled into the strip.

Rolling fold

These planchets are punched with a damaged blanking die, leaving a raised piece of metal on the edge of the planchet. This is not extra metal as the weight of these planchets is the correct weight for the coin. This raised piece is folded over in the upsetting mill and then struck in the coining press.

Rotated dies

Since, under normal circumstances, it is impossible to tell which die has rotated, or perhaps both dies have rotated, the reverse die has been chosen as the offending element. Coins are struck with coin alignment; that is, the top of one side is the bottom of the other side. If a die becomes loose in its holder or was installed with an incorrect alignment, it is said to have rotated. Rotations under 15 degrees in either direction are considered within mint tolerances and have no collector value. The greater the rotation over 15 degrees, the greater the value to collectors. Coins rotated 180 degrees are said to have medal alignment. A couple of recent examples include the 1989-D Congress dollar and the 1988-P Kennedy half, which, by the way, can be found in mint sets.

Rotated hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of a rotation of the hub or die at a point near the center of the design. This rotation can be either clockwise or counterclockwise and affects all design elements, the strongest doubling being around the rim. The most famous doubled die of all, and the one which made variety collecting a force to be reckoned with in the numismatic community, is the 1955 hub doubled Lincoln cent. Its doubling is attributed to a rotated hub. See hub doubled varieties.

(Photos courtesy of J.T. Stanton)

Rotated second strike over a centered first strike

This coin exhibits a dual image on both sides of the coin because it was struck by the dies a second time while remaining in, or partially in, the collar but rotated considerably from the position of the first strike.

Saddle Strike

See Non overlapping double strike.

Second strike doubling from a loose die

This is the first of two exceptions to the rule which says that doubling must show on both sides of the coin. This coin exhibits doubling on the anvil die side of the coin only due to the die being loose and turning between strikes. This type of double strike usually only affects proof coins which are normally struck twice. See also Flat field doubling.

Separated doubled mintmark

This is a sub-category of the RPM in which the two mintmark images are completely separated.

Shattered die

Three or more die cracks radiating toward the center of the die, usually 90 degrees apart, indicates that the die has begun to shatter into several pieces.

(Dies courtesy of Ken Potter)

Single curved clip

These planchets have only one curved clip. The larger the clip, the greater the rarity.

(Coins and Photos courtesy of Ken Potter)

Sintered

These planchets were kept too long in the annealing drum. While in the drum, they became coated with a layer of metal dust which the heat then sintered onto the planchet. These are known with partial, single-sided, and double-sided sintering. See also Copper Wash.

Slag inclusion

These planchets are the product of impurities that gather at the top or bottom of molten metal. When the ingots are poured, slag may become imbedded in the metal and later become part of a planchet. Slag is usually harder than the alloy and strikes up poorly. Slag is darker than the alloy, often black.

Small over large mintmark

This is a sub-category of the RPM in which two different sizes of mintmark punches were used and the secondary mintmark is the larger of the two.

Spiked head die crack

This is a sub-category of the die crack, commonly referred to as a “spiked head.” Though they can be found on most denominations, they are primarily collected on the Lincoln cent. Literally hundreds have been catalogued. Spiked heads were actively collected in the 1960s and 1970s, but waned with the increased interest in doubled dies and RPMs in the 1980s.

(coin courtesy of Karl Krokenberger)

Split – after strike

These planchets split parallel to the faces of the planchet after the strike has been imparted, thus one side shows a coin image and the other side shows planchet striations from the split.

Split – before strike

These planchets split parallel to the faces of the planchet prior to being struck, thus they will show a weak strike on both sides of the coin.

Split – hinged

These planchets have not fully split apart but remain connected by a small piece of metal, or “hinge.” They are often referred to as “clamshells.”

(Image courtesy of Whaden Curtis)

Split collar

Sometimes the collar splits in a fashion similar to a split die. The coin struck from such a split collar is also out of round with two raised areas of metal – one at each end of the split. Both the “collar break” and the “split collar” are collected as “collar cuds.”

Splits: In Coin &/or Planchet (due to excessive striking pressure)

Sometimes when a coin is struck—especially when more than one planchet is involved or it is otherwise struck in error; striking pressure will cause it to split. These splits are unrealated to the Defective Planchet error described above.

(Coin Courtesy of Mark Longas/photo by Ken Potter)

Split die

This is a sub-category of the rim-to-rim die crack. When the rim-to-rim die crack deepens into the die shank, the crack widens, forming a thick line across the face of the coin. There is usually displacement of the design across the crack.

(Die courtesy of Ken Potter)

Straight clip

These planchets are punched from the sheared or sawed end or edge of the coin metal strip.

(Photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Strip, coin metal

These are small pieces of the web. They are small enough to enter the coining chamber and can be struck by the dies. Sometimes they are referred to as “fragments” or “bow-ties” though not all fragments are struck from these small pieces.

Struck off-center

When the collar is jammed in the fully downward position and the planchet fails to be centered between the dies, the result is an off-center strike. The only difference between an uncentered broadstrike and an off-center strike is the degree of off-centeredness. If any portion of the design is missing, it is an off-center strike. Most collector demand for this error is in the 35-65% off-center range. Lesser percentages are acceptable for rarer dates, but larger percentages are usually ignored by the knowledgeable collector.

(Coin and photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

Struck over a different denomination or series

This coin was struck normally and then received a second strike from a different denomination. There are several combinations in this category; however, remember that the second strike must be from dies larger than the planchet, just like the “struck on wrong planchet” coins. A typical example is the “11 cent piece” – a cent struck over a struck dime.

(Coin and Image courtesy of Michelle Lee)

Struck through dropped filling

This coin exhibits an incused image of a letter, digit, or design element due to the filling of a filled die coming loose and dropping either on the die or on the planchet. Under the pressure of repeated strikes, a filling becomes compacted and hard. When it falls out, it retains its shape and transfers it to the planchet.

(Coin courtesy of Larry Allegrina/Photo by Ken Potter)

(Coin and Image courtesy of Daniel D. Bonnett)

Struck through grease filled die

This coin exhibits weak or missing design elements due to the die being clogged with a combination of grease, dirt, and iron filings. There is a rough surface where the design element is missing. Since it is relatively easy to fake this error, only uncirculated coins are considered collectible. This is the most common of all struck through errors.

(Coin courtesy of Walter Flack/Photo by Ken Potter)

Struck through string

This coin exhibits an incused thin line, usually in a wavy or circular pattern, from a piece of thread that curled up on the die or planchet.

Struck through wire

This coin exhibits an incused thin line from a piece of wire or bristle from a wire brush that came between it and the die. A standard piece of equipment in a machine shop is a wire brush or file card that is used to clean the grooves of a file. The pressman periodically uses the brush to clean the press and the dies when they become clogged with grease and dirt. Falling bristles can find their way into the coining chamber and be struck into a coin. These often appear in a U shape and have been incorrectly called “staples.”

(Coin courtesy of Larry Allegrina/Photo by Ken Potter)

Struck through: cloth

This coin exhibits the pattern of the cloth that came between it and the die. Cloth is a very common item around machinery. It is used to wipe grease and dirt away from the dies. Coins struck through cloth, however, are not a frequent occurrence.

Struck through: misc.

This coin may be struck through a variety of objects not included in the classifications above. In fact it is ofte impossible to tell what the object was that fell between the dies and planchet.

(Photo courtesy of Ken Potter)

(Coin courtesy of John AArt@ Bowers/Photo by Ken Potter)

Tapered

These planchets are punched from coin metal strip that has been rolled so that the thickness is reduced sharply, resulting in a planchet that is thinner than normal at one edge.

Tilted hub doubling

This coin exhibits hub doubling that occurred as a result of either a tilted hub or die when the first hubbing was made. The tilt caused only a small portion of the design to be transferred, usually near the rim of the die. The doubling is the strongest toward the rim and diminishes toward the center. The best example is the 1963-D Lincoln cent, which exhibits doubling of the 3 in the date. See hub doubled varieties.

Tilted mintmark

This coin was struck from a die in which the mintmark had been punched at an angle. A tilt of at least 45 degrees is necessary before it is considered collectable.

Tilted partial collar

When the collar jams in a tilted position, the result is a coin with an unlevel split edge. See also Partial collar, Reverse partial collar.

Uncentered broadstrike

This coin also exhibits a larger-than-normal diameter; however it is not evenly centered. The uncentered broadstrike shows all of the coin design, but shows it off to one side.

(Image courtesy of Whaden Curtis)

Unfinished proof die strike

Some circulation strike bullion coins have been struck with obverse dies which were unfinished proof dies. This is confirmed by the fact that they carry the W mintmark which is a proof only mintmark.

Uniface strike

When two planchets rest on top of each other in the coining chamber, the result is one coin with a sharply struck obverse and no reverse and a second coin with a sharply struck reverse and no obverse.

Unplated

These planchets have all of the core material exposed because of a lack of plating.

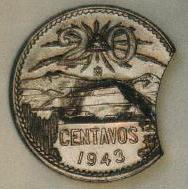

US on Foreign planchet

These coins were struck on planchets intended for foreign coinage. The U.S. Mint has had contracts to produce coins for several foreign countries and some of the U.S. Mint’s suppliers of finished blanks or planchets also produce same for foreign countries.

Weak strike

These coins were struck with lower-than-normal pressure. They are distinguished from die adjustment strikes in the amount of design showing. Weak strikes show the complete design except at the points of highest relief

Wrong metal planchets

These coins were struck on the wrong planchet. Sometimes the wrong planchet is also the wrong metal. This is an area where there is a myriad of combinations. These differ from “wrong stock planchets” in that here there is nothing wrong with the planchets themselves, only that they are struck by the wrong dies. Remember that a planchet larger than the coin’s intended diameter cannot enter the striking chamber. The result is that every current denomination can be struck on a dime planchet, while only dollars can be struck on dollar planchets (excluding the smaller SBA planchets). The most common combinations are cents struck on dime planchets, nickels struck on cent planchets, and quarters struck on nickel planchets.

(Coin courtesy of Ted Bailey)

(Coin courtesy of Jim O’Donnell)

(Photos courtesy of Ken Potter)

Wrong stock planchet

When the wrong coin metal strip is fed into the blanking press, the result is a planchet with the correct diameter but with the wrong thickness and/or alloy.